This post covers the mining escapades of two brothers, Matthew and Samuel Grose born in Redruth Cornwall in the 1760’s and worked at mines in Somerset and Cornwall. They were first written about here.

Recap:

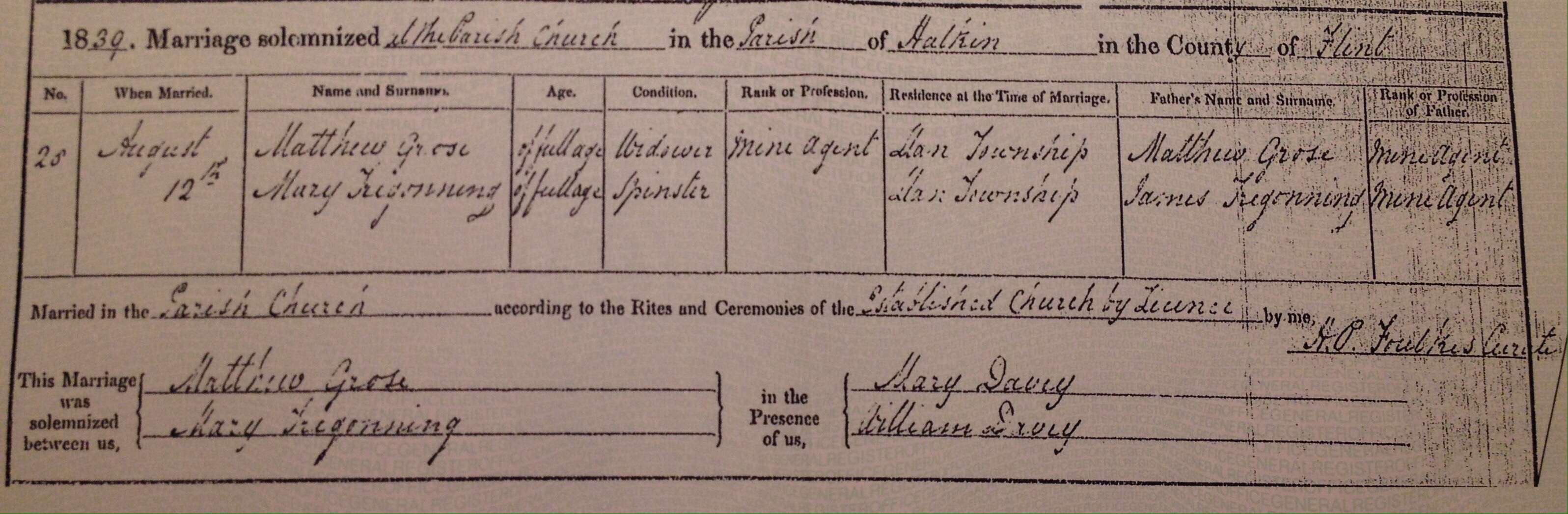

Matthew Grose (1761-1824) is the father of Matthew Grose (1788-1849) who moved to be Captain at Foxdale Mines, Isle of Man.

His brother, Samuel Grose (1764-1825) is the father of ‘the famous engineer’ Samuel Grose junior (1791-1866) who was a pupil of Richard Trevithick and designer of the Cornish engine.

..

Introduction:

After reading these four fantastic books, extra info has been gathered:

- “Men & Mining on the Quantocks” (Second edition) by J.R. Hamilton and J.F. Lawrence

- “News from Cornwall” by A.K. Hamilton Jenkin

- “Mines and Miners of Cornwall (Hayle, Gwinear & Gwithian)” by A.K. Hamilton Jenkin

- “The Historic Landscape of the Quantock Hills” by Hazel Riley (free: here)

The details about Matthew and Samuel Grose in the books are mostly sourced from letters written and received by William Jenkin of Redruth in Cornwall (1738-1820).

William Jenkin looked after the mining interests of the Marquis of Buckingham in Cornwall and developed mining on the Marquis’s Dodington Estate in Somerset.

William Jenkin had a close friendship with Samuel Grose, but an antagonistic relationship with Matthew Grose and this is reflected in his letters. The books interpret this accordingly – hailing sensitive Samuel Grose ‘a Cornish artisan’ whilst outspoken Matthew Grose is deemed the ‘less reputable, impulsive brother’!

Most of the ‘quotes in italics’ in the following timeline are brief extracts from their extensive correspondence with William Jenkin.

…

“Two Men of Very Different Minds”: 1786-1824

CORNWALL TO SOMERSET:

1786: At the age of 25, Matthew Grose leaves Cornwall for Somerset, boldly claiming he is ‘the first miner introduced to seek for Copper at Dodington’ [in recent times]. Matthew begins mining work with a few Cornish Miners on Dodington Common in Somerset. He is then established at the Garden Mine at Dodington in a supervisory capacity.

Relations between the Cornish Miners and locals of Somerset are delicate. Jenkins writes that the local ‘inhabitants seem quite disposed to be offended’.

Matthew’s staff now consists of coal miners from Radstock, Somerset, but he finds them unmanageable and wishes to replace them with Cornishmen, but William Jenkin refuses.

Matthew Grose is overly enthusiastic and unwisely gives the Marquis of Buckingham an exaggerated impression of the value of the veins discovered in Dodington. This annoys William Jenkin and his opinion of Matthew wavers.

1788: Matthew Grose moves sideways to be Captain at the Marquis of Buckingham’s Mine at Loxton, on the Mendip Hills. (His son, Matthew Grose (1788-1849) – is baptised at the Parish church of St. Andrew’s here).

Parish church of St. Andrew’s, Loxton © Copyright John Baker and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence.

1791: Whilst Matthew is in Loxton, his brother, Samuel Grose is appointed senior Mine Captain at Dodington. Some Cornish miners in his employ return to Redruth and it is difficult to attract others to Somerset because ‘the spirit of Mining is high in Cornwall’. Jenkin asks Samuel Grose to give any remaining Cornishmen proper encouragement to stay, or ‘get some of the Somerset young men to become handy’.

Samuel’s ‘famous engineer’ son, Samuel Grose junior (1791-1866) is born at Nether Stowey, Somerset.

1793: The French First Republic declares war on Britain.

1794: Josiah Holdship comes to Somerset seeking the mineral ’emery’. He approaches Matthew Grose at Loxton first, who sends him on to Samuel Grose in Dodington.

1795: Samuel Grose resides at Newhall, near Dodington which has a:

‘colony of unpleasant neighbours… the most profligate and abandoned part of mankind’.

Matthew Grose is still at the Loxton Mine and similarly writes about the:

“…ill-natured prejudice in the behaviour of the inhabitants at Loxton and it’s vicinity against suffering any but themselves to inhabit the county.”

Matthew seems at his wits end about:

“…tenants as could accommodate Shippam Miners with lodging and would not do it.”

1796: Spain declares war on Britain.

1797: A French invasion of Britain is rumoured. Samuel Grose writes that:

‘I cannot think that the French will come here, but I think they will ruin our country by threatening to come.’

The French briefly invade at Fishguard.

1798: William Jenkin holds shares in Wheal Alfred Mine in Cornwall (named after his son).

1799: There is crisis in the copper trade as prices fall.

1800: Samuel Grose’s spirits fall too. Partly due to the imminent failure of the Dodington mine (a pump is desperately required) and also due to the ‘enormous advanced price of the necessities of life’. Poverty has become extreme in Somerset and Cornwall for working people, including miners.

After a woman (about to be arrested for theft) hangs herself in Samuel Grose’s garden, he writes:

“Glad should I be if circumstances should alter so that my removal was nigh from such bad people and such a disagreeable house as Newhall is at this time. I do not believe we can live there. Let the consequence be what it will.”

and

“I would not have my children frightened by this shocking affair, not for all the Gold in the Universe.”

Ruined building at New Hall. © Copyright Nick Chipchase and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

Samuel desires to move to the Counting House in Dodington (the mine company’s headquarters), but understands ‘it would require £20 to fit it for a dwelling’. Also the mine is unprofitable and closure inevitable.

1801: Jenkin writes to a friend about Samuel Grose:

“…poor Capt. Grose appears to be falling back again. His doctors seem to think that his native air might be of service to him. In that case I could take him back to Cornwall with me, after going to Dodington to supervise the closure of the mine.”

Jenkin also writes directly to Samuel:

“Thou shall not want for anything that I can command or procure – therefore write me freely as one Friend should to another”

Jenkin makes plans to install Samuel as Captain at Wheal Alfred Mine back in Cornwall.

He writes to Samuel (about Wheal Alfred Mine and Matthew Grose):

“Thy brother Matthew had set his mind on this appointment for himself but the preference is given to thee. I hope for the sake of his Family that a place will be found by and for him also, but I am sorry to observe that poor Matthew does not make many friends amongst those who would be most likely to have power to serve him. He is too great a talker and too full of himself. A little disappointment may probably be in the ordering of Providence…”

and

“The mine which Matthew is in is likely to go down. I wish he had so good an opening for future employment as thou hast – but he has not thy abilities to recommend him.”

…

After fourteen years, mining at Dodington ceases in 1801, with Samuel Grose and a dozen men departing. William Jenkin laments about the ‘scattered bunches of rich ore’ and supposes that at a deeper level it will be more ‘regular and collected’. A powerful steam engine is required to work the deeper, richer veins, but no investment is forthcoming.

Also in 1801, change is afoot internationally as the fighting with France dwindles and a peaceful conclusion draws near. Jenkins writes:

“After the scourge of War and famine which has long threatened the inhabitants of this land, this is the method that they take to manifest their thankfulness for so great a deliverance. Illuminations, Shouting, Bawling, Huzzaing, Cursing, Drinking, Squibbs, rockets and fire balloons are poured out and scattered through Earth and Air, while the poor and needy are neglected and forgotten.”

…

BACK IN CORNWALL

1802: The Treaty of Amiens temporarily ends hostilities between the French Republic and Britain.

1803: Now back in Cornwall, Samuel Grose is in better spirits as Captain at Wheal Alfred Mine with an engine. “The water is very quick… but I believe we shall be able to endure… I have now a better opinion of Wheal Alfred than I ever had.”

1804: Spain declares war on Britain (again)

1805: Thomas Poole from Nether Stowey in Somerset considers promoting a reopening of the Buckingham Mine at Dodington. (Thomas Poole is a great friend of the poets Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth and for some time they reside closely) .

1806: The eminent inventor and chemist, Humphry Davy is approached for capital and geological advice regarding the peculiar shell limestone formations in Dodington. He responds advising that:

‘Miners from Alston Moor and Derbyshire would understand your Country [mines] better than Cornish miners.’

Humphry Davy declines to ‘adventure’ (invest in the mines) because he is saving to embark on a scientific expedition to Norway, Lapland and Sweden.

Pottery mogul Josiah Wedgwood II is also approached to invest, but he’s averse to adventuring money on Somerset Copper mining.

However, the high price of copper attracts interest from other investors and mining again at the Buckingham Mine in Dodington becomes a possibility.

1807: Thomas Poole meets with William Jenkin and Samuel Grose for advice on mining matters. Samuel won’t be persuaded back to Somerset as he is now the Mine Agent at ‘a truly great copper mine’ (Wheal Alfred in Cornwall). Jenkin advises that Samuel Grose might be able to give direction by travelling to Somerset three or four times a year. Jenkin does not get directly involved either, however remains as an active well-wisher and helps recruit Cornish miners for the venture in Somerset.

1808: Thomas Poole travels to Cornwall again to see ‘the mines and gigantic machinery employed about them.’ Jenkin doesn’t meet with him – now weary of the Somerset men merely talking about mining, with no action.

1810: Sweden declares war on Britain

1811: Ardent Methodist, Samuel Grose and John Davey (Mine Agents) begin a Sunday School at Wheal Alfred for 250 to 300 children after observing the:

“…profligacy of the Children of many Labourers in that Mine, -and particularly of those who cannot read.”

1812: William Jenkins writes:

“There is too much Copper bringing to Market for the demand”

and of the Anglo-American war of 1812:

“The American War is a great Evil to the Mining Interest in Cornwall. The price of Copper has been gradually declining as the prospect of Peace receded.”

1814: Proposals are made for reworking Herland Mines near Gwinear. According to William Jenkin, his old nemesis, Matthew Grose, has written “a great, blown-up prospectus” .

“Matthew Grose does not, in my opinion, possess that solid Judgement nor that thinking deliberate turn of mind which I consider an essential ingredient to make a Captain fit to direct so weighty an undertaking. One who can indulge himself in what he calls good living so as to become even now unable to go to the bottom of Wheal Alfred, shall not be the Captain of my choice. I do not think he is truly careful of speaking honestly and truly so as to give his employers clear and honest answers to their enquiries – in short he is not Sam, but Matthew Grose – two men of very different minds.”

1815: Matthew Grose and Richard Nicholls proudly return from London with a long list of Adventurers prepared to invest in the Herland Mines. They specify certain conditions about how they are to be paid. They’ve also discovered a shallow level of Silver in the mine that was overlooked in the former working.

William Jenkin grumbles:

“How it may turn out is past my judgement to say – but I don’t feel very sanguine [optimistic] about it.”

Whilst things are possibly looking up for Matthew Grose, his brother Samuel Grose has been under pressure and has run up a debt of £12,000 on Wheal Alfred because…

“…willing to comply with the clamorous demands of some of the Adventurers, [he] kept out of sight some heavy bills for coals, timber, and other articles in order to make dividends.”

Jenkin ‘trembles for the consequences’… should this mine go down’ with 1200 men, women and children employed there. He suggests it is the secret wish of some for Wheal Alfred to go down because it would cause copper prices to rise again.

1816: In February, Richard Trevithick’s famous, powerful pole-puffer engine is set to work at Herland Mines.

However, by October, Jenkin writes that:

“The Herland business has been so badly managed that the Mine has been stopped for want of money.”

200 labourers are turned idle.

“I wish it may be the last time that London adventurers become directors and managers of Cornish Mines.”

Meanwhile, Samuel Grose is called to write an account of the Buckingham Mine in Dodington, Somerset for newly interested adventurers, attracted by Thomas Poole again.

Also, 1816 was the year without a summer, with crop failure and food shortages across Britain and beyond. Welsh families became refugees, travelling and begging for food. Global temperatures had decreased by around 0.5°C, possibly due to a volcanic eruption in the East Indies the previous year.

…

1817: Things seem to have gone from bad to worse in Cornwall. Jenkin writes that:

“The two Parishes of Phillack and Gwinear are very populous, chiefly Miners, and are, I believe, more distressed than any other district in this County, for there is not now one Mine in either of the parishes to give employment to them.”

…

BACK TO SOMERSET

1817-1820 A new shaft is sunk and an engine-house is erected at Beech Grove, behind Dodington House in Somerset.

Beech Grove Engine House © Copyright Nick Chipchase and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

1820: After an absence of twenty seven years, Matthew Grose returns as Mine Captain to Dodington. He supervises the installation of a Boulton & Watt engine in the Beech Grove house.

Shortly afterwards, Matthew requests that the engine be removed from Beech Grove and re-erected at the Sump (Glebe) Shaft to cope with an influx of water.

Matthew Grose writes to John Price on 25 February 1820…

“I am happy to inform you for his Lordship’s information that our prospects in the mine is very good…”

and

“The great increase of water is not a bad symptom, its generally found in all mines the more water, the more ore. I believe shares in this mine may be got at a very easy rate as the pockets of some of the adventurers is very much exhausted, and will not well be able to encounter the expense of removing the engine.”

Disputes arise between various shareholders with the Marquis of Buckingham pressing for a revision of terms and other Adventurers wanting to suspend operations as costs mount. Thomas Poole exercises proxy votes for his friends, forcing the minority to continue. He remains in control for another year.

The engine is moved to the Glebe Engine House as per Matthew Grose’s request. Although good quality copper ore is raised, the mine remains unprofitable.

Glebe Engine House © Copyright Chris Andrews and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

The Marquis is offended. He strongly opposed the moving of the engine because it would no longer be on his land, so in the event of closure he will find it harder to secure new adventurers (investors). He blames Matthew Grose (as Mine Captain) for orchestrating the manoeuvre.

Matthew Grose now faces impending closure of the uneconomical mine, loss of earnings and the wrath of an antagonistic Marquis.

Matthew writes to the Estate Steward:

“I have learned with some concern that I am discredited with you… for removing the engine without his Lordship’s leave for doing so… I hope no blame can possibly be attached to me.”

Matthew Grose then goes onto explain his many technical and economic reasons for moving the engine from Beech Grove to the Glebe House and the unavoidable costs involved.

The Marquis’s wrath continues as he expresses more displeasure – he’d been told there were manganese deposits in his mine at Dodington, but these have proved non-existent.

Matthew Grose tries to explain a convoluted catalogue of errors (including an adventurer dying en-route to the mines). He insists the lack of manganese isn’t his fault and blames Richard Symes for mixing up samples of ore:

“Mr Symes says now, the samples he sent must have come from Loxton” [not Dodington]

In August 1820, Matthew tries to restore relations with the Marquis by sending him a box of mineral specimens:

“…esteemed valuable acquisitions…. better collected for a grotto than the cabinet.”

1821: Work ceases at the uneconomical Buckingham Mine in Dodington after an expenditure of £20,000 and paltry sales of ore of £2,500.

Matthew Grose writes to the Marquis, saying he recommended the:

“Company to stop the mine altogether rather than continue to work with it in a paltry way. “

He also says:

“I believe that no company that was engaged in mining business was so completely ignorant of the principles of mining, as the Buckingham Mining Company, nor no mine was ever worked in such a shily-shaly way.”

Matthew’s comments about his employer result in his dismissal from the company. He laments:

‘…this extraordinary and unexpected event originated from the belief that I am more inclined to serve his Lordship than the company; though what produced this belief, I know not’

Matthew Grose is instructed to leave the house where he and his family live. No wages are to be paid until he’s complied.

Stubbornly, he remains in residence and becomes captain at a small mine 25 miles west of Dodington (likely Luccombe, or similar in the Alcombe-Wootton Courtenay district).

Matthew Grose writes letters to Thomas Crawford, pleading for employment at the Dodington Mine:

‘no person knows the mine as well as myself’

Crawford responds that:

‘You were the company’s servant and as they have suspended working the mine and do not choose to continue you in their service, I do not know in what way I could help you.’

Matthew Grose is not easily silenced and in June 1821, he indignantly writes to Thomas Crawford again:

‘what right has the company to sell gravel from the mine and carry off so much without making acknowledgement to his Lordship?’

and

‘I keep the keys of the counting house, the office and materials house… A small stipend [salary] with the little I receive from the mine in the west will serve to keep my head above water. I ask no more till it is settled.’

In September, five months after his dismissal, Matthew is offered his wages, only payable up until when the mine had ceased work. He rejects the offer, demanding his salary right up until September. He also rejects their demand that he pay rent on the house.

1822: In August the company surrenders the mining lease. Some adventurers remain interested and want to continue some operations. The Marquis obtains a new report on the mine from Alfred Jenkin and Captain Francis, but it is unfavourable and deters investors.

Matthew Grose remains steadfast and faithful to the mine, despite failing health and an empty pocket. He writes a new prospectus, desperately trying to promote for a new company to rework the Dodington mine. Refusing to return to Cornwall, he lingers on in poverty at Dodington.

1823: Matthew wins the interest of Charles Carne of Exeter who liaises with Matthew Grose’s son John.

Carne applies for a mining lease at the Buckingham Mines, Dodington, but struggles to agree terms.

1824: In February, Charles Carne arranges a meeting with interested parties at the Royal Inn in Bridgwater to raise capital for a new engine for Dodington. Unfortunately the meeting does not happen because Charles Carne has been imprisoned in Exeter ‘by means of a most unlucky adventure in a tin mine in Cornwall.’

According to the book, “Men & Mining on the Quantocks (by J.R. Hamilton and J.F. Lawrence)”, Matthew Grose dies as a ‘starving pauper’ in ‘grinding poverty’ and is buried at Dodington Churchyard on 11 May 1824.

This date concurs with Matthew’s burial record in 1824 and the information from his Memorial which was erected in Gwinear, Cornwall.

…

Conclusion:

Matthew and Samuel Grose’s mining adventures (and misadventures) show the struggle between the reality of mining economics and the optimism of miners.

In the book, “The Historic Lanscape of the Quantock Hills”, Archaeologist, Hazel Riley pays tribute to Matthew Grose’s final bold project:

“The Glebe engine house survives virtually intact to its original roof level. The scatter of red tile fragments around its base shows that it originally had a tiled roof. A large infilled shaft, some 16m in diameter, lies to the south of the engine house and spoil heaps lie to the east. The thick bob wall was on the southeast, the cylinder opening, with a brick arch, was in the northwest wall. Some good quality copper ore was raised from these deeper levels: 100 tons of ore from the Buckingham mines was sampled and shipped from Combwich in 1820 when it was described as ‘rich and of prime quality’ (Hamilton and Lawrence 1970, 62). The engine houses are remarkable testaments to the business acumen of Tom Poole and the practical enthusiasm of Matthew Grose, the mine captain. The Glebe engine house is the oldest intact beam engine house in southwest England (Stanier 2003).”

Glebe Engine House and ruined Miners’ Store © Copyright Nick Chipchase and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

…

Resources and Further Reading:

Books:

- “Men & Mining on the Quantocks” (Second edition) by J.R. Hamilton and J.F. Lawrence

- “News from Cornwall” by A.K. Hamilton Jenkin

- “Mines and Miners of Cornwall (Hayle, Gwinear & Gwithian)” by A.K. Hamilton Jenkin

- “The Historic Landscape of the Quantock Hills” by Hazel Riley (free: here See pages 148-150)

Websites:

…

As always, please comment or make contact about this post!